Sixty years ago this month, a group of young members and volunteers of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized an impressive voter registration day in Selma, Alabama. “For the first time in our history a major social movement, shaking the nation to its bones, is being led by youngsters,” wrote historian Howard Zinn at the time. This month, we show you a series of photos by John Kouns of Freedom Day in Selma in 1963. Although we don’t have photographs of Crystal City, Texas, we offer you a photograph by Harry Adams where the newly elected mayor of Crystal City, Juan Cornejo, came to the Freedom Rally in Los Angeles in May 1963, and we tell you a part of the Crystal City voting revolts when a voting-poll drive led to a sweeping victory of five Mexican American candidates. We also offer you a link to the full series of videos with the Farmworker Oral History Dramatization Project with stories of participants of La Causa and photographs by Emmon Clarke and John Kouns. We let you know about the work of Madre Monte, a women’s art collective from San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia, and their interest in Richard Cross’s photographs.

Freedom Day, Selma, 1963

By José Luis Benavides

Last month, we talked to historian Dr. Peniel E. Joseph, who came to campus this summer to talk about his book The Third Reconstruction. He is currently working on a new book focused on 1963 as a key year in the history of the Black Freedom Movement. We wanted to show him the photographs that are part of our collections and cover many events of 1963. We showed him images by John Kouns of one of the important events that year, Freedom Day in Selma, on October 7, 1963. The events of that day were documented hour-by-hour in the book SNCC: The New Abolitionists by Howard Zinn—then a young historian who taught at Spelman College and got involved in the movement.

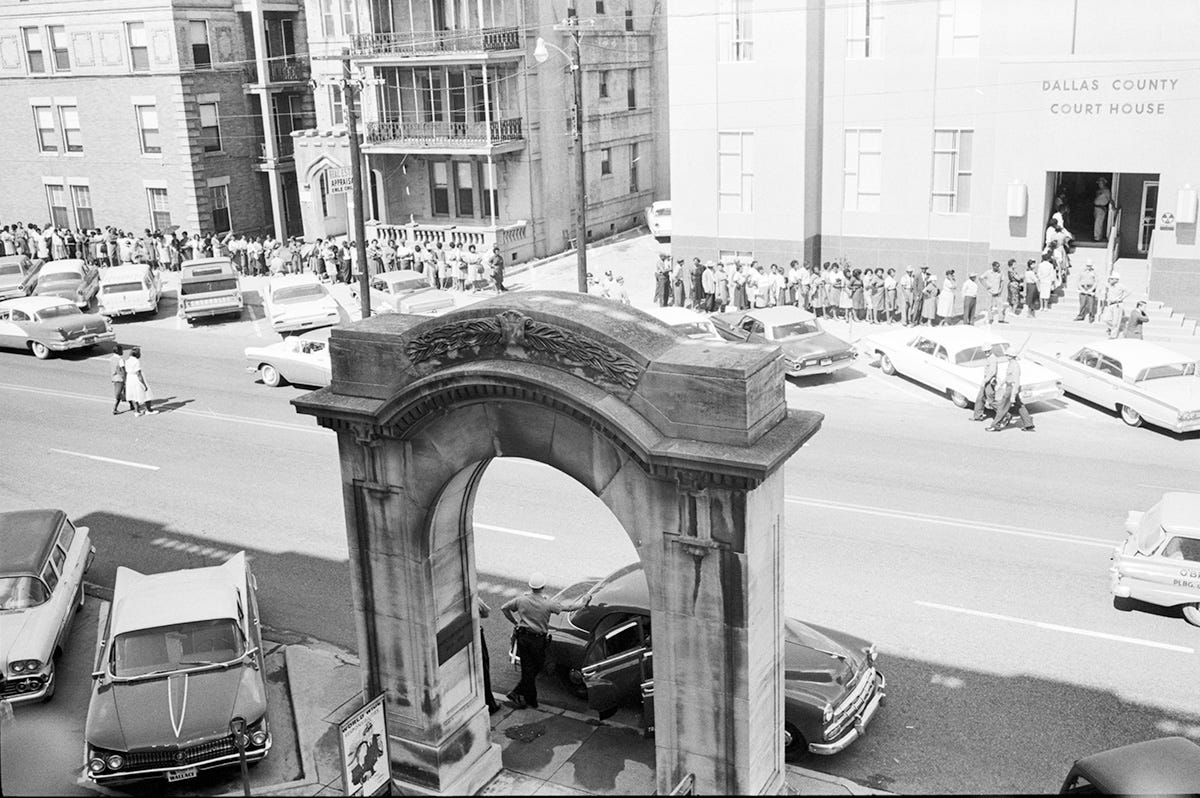

The voter registration drive in Selma started in February 1963 and was led by Bernard Lafayette and his wife Colia Liddell, organizers of SNCC. In Dallas County (where Selma is located), fifty-seven percent of the population was African American but only one percent of eligible African American voters were registered to vote. The reaction to the registration campaign was violent by white groups and law enforcement. Between Sept. 15 and Oct. 2, 1963, “over three hundred people were arrested in connection with voter registration activities,” wrote Zinn. Many, including Lafayette, were brutally beaten and/or hit with electric cattle prods.

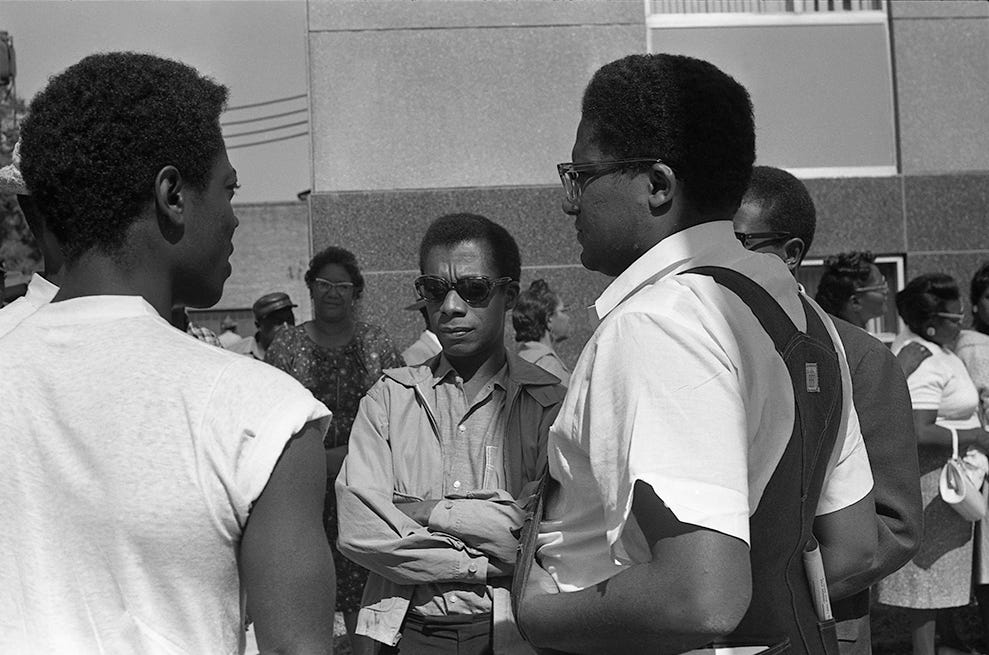

Risking their lives and their jobs, approximately 375 people waited in line all day, standing, with no food or water, prohibited from leaving even for a bathroom break, and monitored by storm and state troopers. At the end of the day, only between 12 to 20 people were able to apply to register, recalled writer James Baldwin, who attended the event with his brother David. In Alabama, people couldn’t just be registered, wrote Howard Zinn, they had to apply by filling out a long form with 21 questions, like ‘Name the duties and obligations of citizenship.’ Then, the registrar would ask oral questions, such as “Summarize the Constitution of the United States,” and three weeks later people would receive a postcard with passed or failed.

In Dallas County, “applications were accepted on the first and third Mondays of each month,” according to Zinn’s book. He estimated that at a rate of 35 per Monday (assuming all passed), it would take 10 years for African Americans to make up the 7,000 plurality held by white registrants in that county. “The real drama is the fact that the people can’t vote and the government won’t help them and that they’re living in a police state with the collusion of the federal government,” concluded Balwin in an interview with Fern Marja Eckman recently published in The New Yorker.

Juan Cornejo and the Crystal City Revolt of ‘63

Melinda Mata, granddaughter of Juan Cornejo, informed us a few years ago that her grandfather appeared in a 1963 Freedom Rally image with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. next to Councilmembers Gilbert Lindsey and Tom Bradley. On April 2, 1963, Cornejo and four other Mexican-American candidates were elected to the city council in Crystal City, Texas, in a political, racial, and civil rights earthquake that became known as the Crystal City Revolt. Despite the fact that Mexican-Americans outnumbered whites four to one, whites had run the city government since the town was established. The April election challenged the racial power structure of the city, with Juan Cornejo as the most visible symbol as he became mayor of the city. Cornejo and council member Antonio Cárdenas were invited to Los Angeles by the Mexican American Political Association. “One of the beauties of democracy,” said Cornejo to the Los Angeles Times reporter Rubén Salazar, “is that about three months ago the Crystal City clerk wouldn’t give me the necessary blank so I could file for political office and today I’m mayor and using Mayor Yorti’s car.”

Like the African Americans in the South, Mexican Americans in Texas were prevented from registering to vote. All citizens who wanted to vote were required to pay a poll tax of $1.75. But a successful poll-tax drive spearheaded by the Teamsters and the local chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speakeing Organizations (PASSO), led by Juan Cornejo, made Mexican Americans the majority of registered voters for the first time. The victory of the five Mexican Americans attracted national and international attention. Unfortunately, the established white power structure turned against them quickly. Council member Cárdenas was fired from his job, others saw their salaries reduced to half. Texas Ranger Capitan A.Y. Allee refused to return the only key to the council chambers to Juan Cornejo. Threats escalated and Cornejo flew to San Antonio and filed several complaints. Cornejo finally returned to Crystal City, but the attempts to sabotage the new government continued unabated.

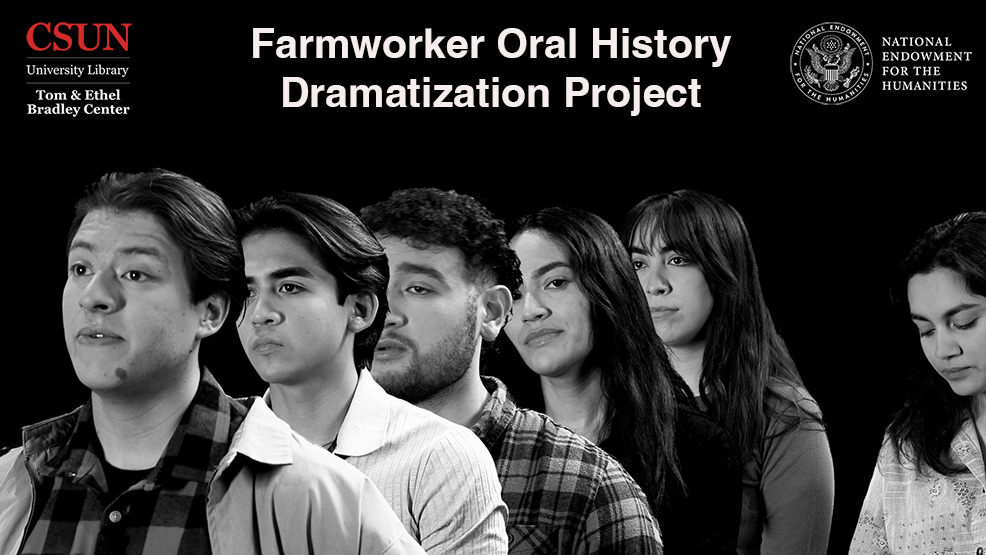

Farmworker Oral History Dramatization Project

We have finished our three short films that form our Farmworker Oral History Dramatization Project. This film series, directed by Theatre Professor Doug Kaback, is a dramatization of selected segments of several oral histories of participants of the Farmworker Movement. It uses photographs by Emmon Clarke and John Kouns as a background to the actors's monologues, providing visual context to the stories. Marta Valier from the Bradley Center and 18 brilliant students and alumni from Theatre, Art, and CTVA created this project under the supervision of professors Doug Kaback, Jose Bautista, and José Luis Benavides.

In Part 1 (Joining the Union), Bobby de la Cruz (Jesús Venegas Vázquez) tells how he and his mother, Jessie de la Cruz, joined the movement.; Carmen Hernández (Alejandra Guzmán) tells how all her siblings did chores to help her parents, Fina and Julio, who were active in the union; the Saludado sisters, María and Antonia, (Ruby Hernández and Eileen Ávalos) recount their experience working in the fields and why their family joined the union. Joe Serda (Aldeir Vázquez) explains how his family experience in the fields and his daughter's activism made him realize he needed to join the union.

In Part 2 (Becoming an Organizer), the Saludado sisters, María and Antonia (Ruby Hernández and Eileen Ávalos) remember the beginning of the strike and how they became non-violent organizers. Joe Serda (Aldeir Vázquez) explains how he organized workers to join the union and to get information from the company. Carmen Hernández (Alejandra Guzmán) tells how her entire family managed to survive with union support and participate in the strike at the same time.

In Part 3 (The Action), Carmen Hernández (Alejandra Guzmán) tells how she abandoned school but found her path working for the union, which became a source of community strength for working families; Bobby de la Cruz (Jesús Venegas Vázquez) tells how he organized a grape boycott at the cafeteria of Fresno City College and joined his mother to picket in front of Safeway's headquarters in San Francisco; Richard Chávez (Nicolás Guerrero) explains the spiritual philosophy of his brother César so he could help bring about change and the grape boycott's 58-month journey to the signing of the contracts.

Madre Monte and Richard Cross

Madre Monte, the women's art collective from San Basilio de Palenque in Colombia, reached out to the Center recently. They were researching our digital collection with Richard Cross’s images of Palenque in the 1970s. We have had a productive conversation with the collective and we are hoping to establish a long-term relationship with the group. We want to thank Ernestina Miranda for helping us identify her mom, Celestina Obezo, in this photo by Richard Cross. She is also the co-director, with Mar Ajé, of the short documentary Ngubá (goober or peanut). You can watch the trailer in Spanish below. Madre Monte is working on an art project using images by Richard. We’ll update you here. Their work is amazing and much needed.