Women will not be silenced

By Gillian Morán-Pérez

This year, Independence day rang a heavier, morose tone for many Americans. While some celebrated with barbecues and fireworks, others felt the suffocating weight of the Supreme Court’s decision. The verdict should prompt us to ask: Which Americans are entitled to freedom? To whom does Independence day apply?

The decision to overturn Roe v. Wade tells the American public that women are not entitled to freedom. The battle for reproductive rights and reproductive justice has come a long way. Women will not stop fighting, as we heard California Congresswoman Maxine Waters raise her voice at the cameras on that fateful day and affirmed that women will have control over their bodies, especially Black women.

Waters’ remarks highlight the consequence that restricting abortion rights has on Black women. A Texas Tribune article underlines that African American women die during pregnancy or childbirth at a higher rate than any other group in the U.S, they experience the most maternal health complications, and they represent 40% of women who get abortions. In the words of Professor SaraEllen Strongman, who wrote an Op-Ed for the Washington Post, “... abortion had long been a strategy of survival and resistance for Black women. Historians have revealed that abortion even enabled some semblance of self-determination during slavery.”

We want to highlight images of Black women behind the movements for abortion rights. Not only has Maxine Waters been adamant in fighting for reproductive rights, but so was Congresswoman of New York Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman elected to Congress in 1969. When Chisholm entered office, she was known for leading the fight for abortion rights by dismantling the notions carried by White men that abortions were “genocide” for African Americans. As Strongman writes, Chisholm refuted in her book Unbought and Unbossed arguments that birth control and abortion were “plot[s] by the white power structure to keep down the number of blacks.” She also noted that she only ever heard men espouse these views, writing, “To label family planning and legal abortion programs ‘genocide’ is male rhetoric, for male ears. It falls flat to female listeners and thoughtful male ones.”

Waters and Chisholm remind us that nothing will silence a woman's voice.

Farmworker Movement Spotlight: Emmon Clarke

By José Luis Benavides

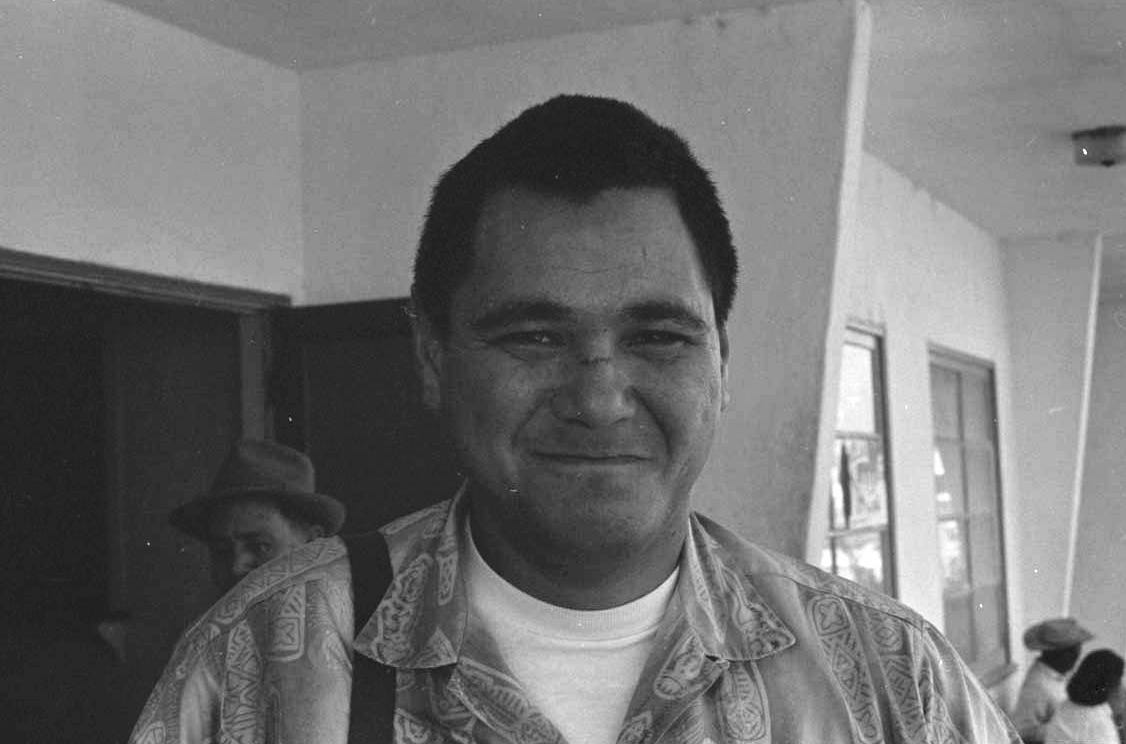

In the process of researching and preparing the metadata for our Farmworker Movement Collection, we have been pleased to see emerge some photos of one of the photographers whose collection we are working on, Emmon Clarke. Recently, we had the opportunity to talk to him and his wife Judith and we learned more about his experience with the farmworker movement and what motivated him to volunteer as a photographer for the movement’s newspaper, El Malcriado.

Emmon Maika'aloa Clarke (1933) was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, and became interested in photography at an early age inspired by images in the magazines Look, Life, and Saturday Evening Post. “I wanted to be one of those guys,” he said. In 1950, He joined the army two weeks before the Korean War started. Later, he built a career in the military. In 1962, he married his wife, Judith, who persuaded him to move initially to Dinuba, California, where she grew up. They lived with her parents for a few months until she got a job as a social worker in Tulare County for a year (1963-64), where they saw the emerging farmworker movement. Because of Judith’s work, they moved to Eureka and later to Moran. While they were living there, Emmon decided to visit Delano and explored the possibility of volunteering for the National Farm Workers Association. On October 15, 1966, he photographed picketer Manuel Rivera being run over by a truck at the Hourigan-Mosesian-Goldberg Company packing shed. That event persuaded him to stay and volunteer as a photographer and later photo editor of El Malcriado for several months. He documented the union’s activities on the picket line, in meetings, at rallies, and in the labor camps of the San Joaquin Valley and briefly in Texas.

Here is what Clarke told Richard Street about this event:

“During the picketing, Manuel Rivera, a pleasant middle-aged man with a large family who lived near the Delano union office [and had been one first rose workers in McFarland to support la causa] was run down by a truck. Hearing the screech of breaks and cries of pickets, I wheeled around and caught the seriously injured Rivera as he lay under the wheels of the truck. It was right in front of me, and I shot it with a 28-millimeter lens. I was running backward, shooting as it all happened. . . . I developed that roll of film in the trunk of my car . . . then headed to Dinuba and printed the pictures in a darkroom at my father-in-law's house. As a result of those photographs, I became a part of El Malcriado and moved from the barracks into a tract house on the outskirts of Delano, where the newspaper was published. For my work, I received the usual five dollars a week. food, and board, but also an unlimited supply of bulk-loaded black-and-white film.”

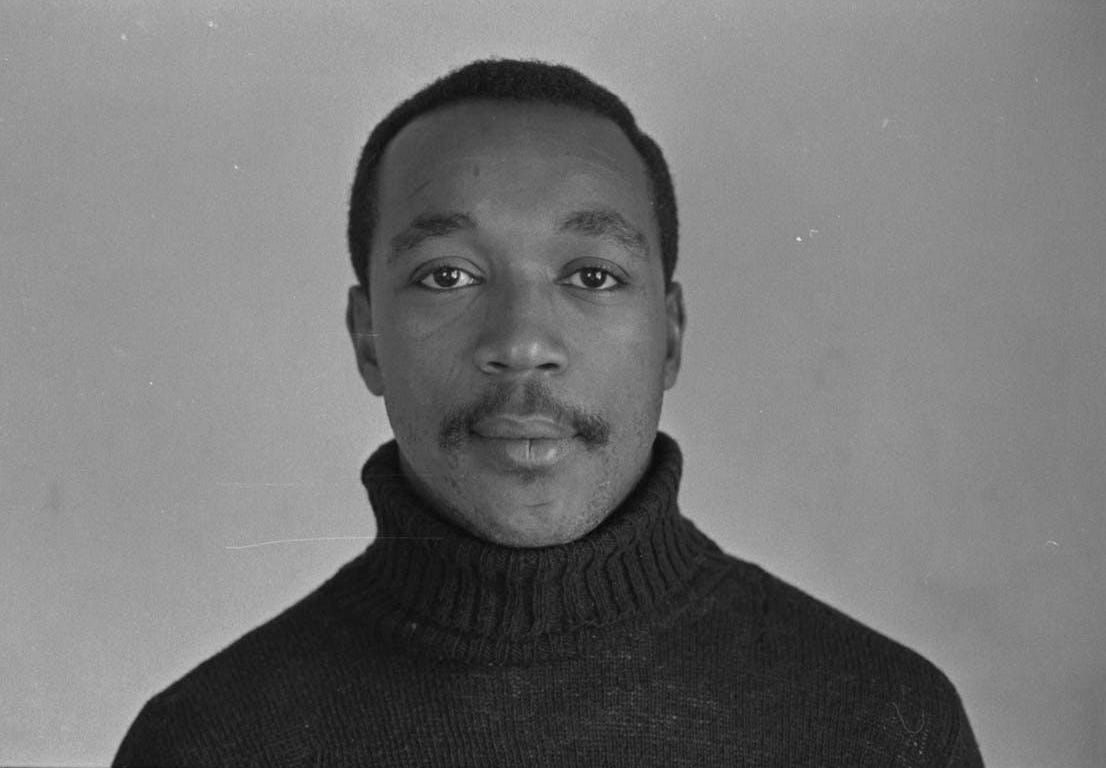

Farmworker Movement Spotlight: Mack Lyons

Many of Clarke’s photos are portraits of people. Fortunately for us, these portraits serve as points of entry to the amazing stories of the many individuals who contributed to La Causa. This is the case with Mack Lyons.

Mack Lyons (1941-2008) was born near Dallas, Texas to parents who worked in the Texas cotton fields, and later settled in California in 1965. He worked in Bakersfield driving a cotton-picking machine and a tractor. Later he took a job at the grape fields of DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation in Arvin. After meeting NFWA organizer Marshall Ganz, he joined a delegation of workers who were arrested after refusing to leave a meeting with Robert DiGiorgio. After being released, they returned to DiGiorgio’s offices and were arrested again. Their protests forced DiGiorgio to hold elections. From 1966-1969, he worked in the valley organizing pickets and was elected as a union representative at the DiGiorgio Corporation for a very diverse group of workers composed of Mexicans, Filipinos, Puerto Ricans, and African Americans in Arvin. Lyons soon became the only Black member of the UFW executive board. In 1971, César Chávez sent Mack and his wife Dianna Lyons to work in Central Florida’s citrus belt in Avon Park, where local workers and the UFW had negotiated an important contract with Minute Maid, the orange juice maker owned by Coca-Cola. Mack and Dianna Lyons worked together and renewed the contract in 1975 before going back to Sacramento to lobby for legislation to fund California's agricultural labor bill.

In Honor of Roland and Deborah Charles

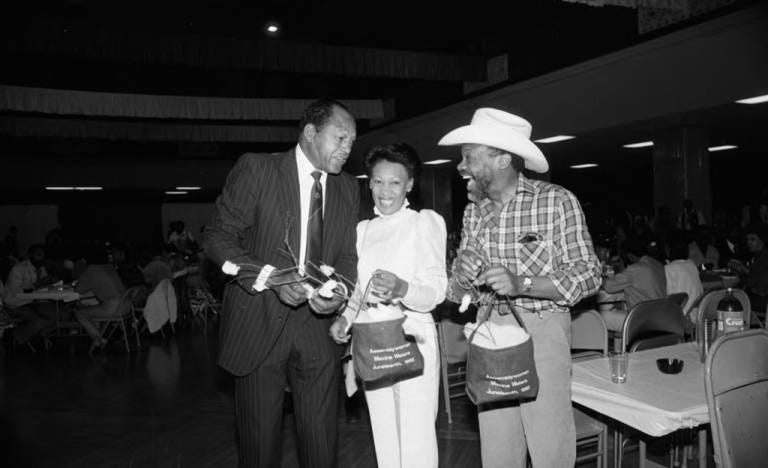

Last month, Carolyn Wilson and Jannette Williams, sisters of the late Deborah Charles, donated to the Bradley Center the part of Roland's collection that was still in the hands of Deborah—negatives, prints, and some framed photographs and art. Roland Charles was the founder and executive director of the Black Photographers of California and the Black Gallery. His photographs have been included in numerous national and international exhibitions as well as in a number of books and numerous private collections including the California African American Museum, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and The Getty Center for the History of Arts and The Humanities. He was a founding member of the Jazz Photographers Association and of Photo Friends of the Los Angeles Public Library. Roland also documented life in Bob Town, Louisiana over a period of more than thirty years. Three people from the Center received this valuable material: archivists Beth Peattie and Keith Rice, and the Center's director, Dr. José Luis Benavides.

You can see a sample of Roland Charles's photos here.